Legging In: A Primer on Trading Complex Derivatives

Complex orders are valuable instruments for a variety of trading strategies, such as hedging price volatility on large market exposure. Principled traders understand the market structure and invest in a capable tech stack to identify opportunities to uncover alpha. Trading desks focused on these derivatives must be comfortable with complexity.

With complex orders, the variety of types and complexity of their mechanics require an intimate understanding of how they’re traded on options and futures markets. From order types to order matching—and accessing the necessary data to leverage them—learning how they work can help even a seasoned trading team identify new opportunities for their trading infrastructure and methodologies.

Types of Complex Orders

Complex orders include simultaneous bids and/or asks of derivatives contracts. A complex order containing individual orders, or “legs,” of long and short positions are called spreads. Since this order type is so prevalent, “spreads” have also become a misnomer for complex orders overall. However, orders that only include bids or asks, not both, are non-spread orders and exist in both options and futures markets. While this complexity enables a long list of order variations, strategies have driven the popularity of particular complex orders.

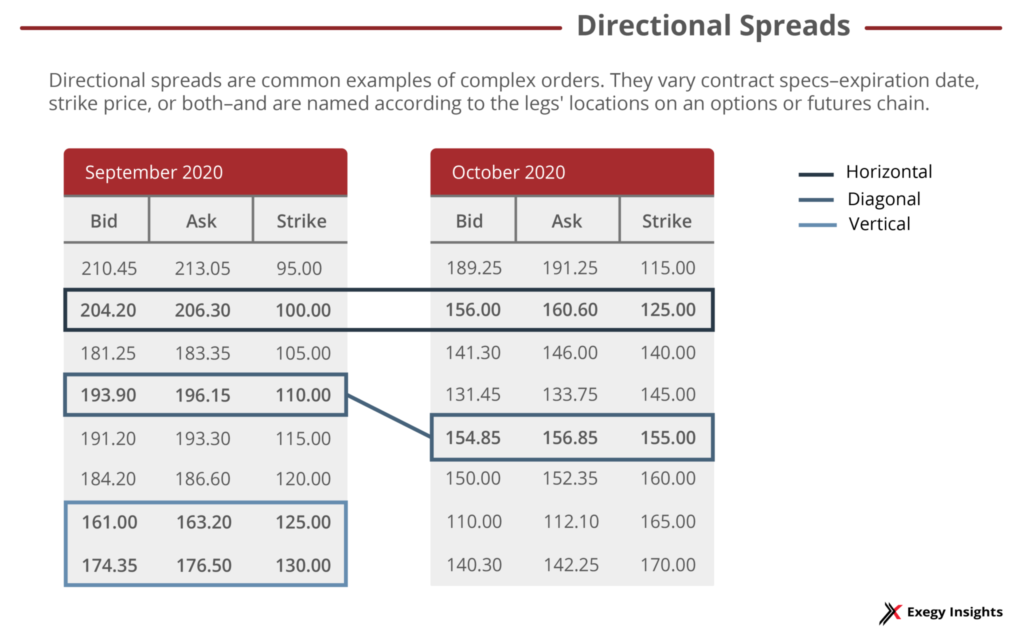

Types of complex orders vary according to the part of the contract specification a trader seeks to hedge. Hedging according to strike price and expiration date are common, but complex orders can also include dissimilar underlying assets and specifically for options, dissimilar types of orders (i.e. call vs put). Directional spreads are common examples for options and futures that vary the contract specs–expiration date, strike price, or both. Selecting each spread type is based on speculation of price direction, when it will change, or by how much, and they’re labeled as horizontal spreads, vertical spreads, or diagonal spreads depending on the legs’ locations on an options or futures chain.

Straddles and strangles are options-specific order types that combine a call and put contract. They’re relatively simple since this order ratio is one-to-one. Additionally, they fall outside of spreads since they hedge through call and put contracts rather than long and short positions. The main difference in these orders is that strangles vary legs by strike price.

Complex orders based on dissimilar underlying assets are not uncommon for commodities futures. Since contracts exist for raw commodities (e.g. oil or milk) and their processed products (similarly, gasoline or cheese), traders can hedge against risks to specific parts of a supply chain. Likewise, intermarket spreads take long and short positions on related assets such as gold and silver to speculate on the relative value of the contracts.

The varieties of orders are vast for both types of derivatives so understanding goals and risk tolerance is important to identifying the best type to use.

The Books for Trading Complex Derivatives

Simple, or outright, contracts outline strike price and expiration date in an options or futures chain. Complex orders not only require these specifications for the underlying contracts but must address details on the ratio of contracts as well. For example, a vertical spread order to buy 100 calls and sell 300 calls of Apple at varying strike prices would be expressed as a 1:3 ratio. To fill the order, it must be executed within the set strike price and ratio.

Table 1: Example of complex order specifications

| Order No. | Legs | Symbol | Side | Ratio | Expiration Date | Strike Price | Class | Bid | Ask |

| 00001 | Leg 1 | AAPL | Buy | 1 | March | 260 | Call | 1.25 | 1.28 |

| Leg 2 | AAPL | Sell | 3 | March | 270 | Call | 1.30 | 1.32 |

The price at which a complex order is bought or sold on an exchange is based on the net prices of the best bids and offers of the single legs in it, leading to a figure called the synthetic BBO (SBBO). For example, if the BBO on an exchange for the example spread listed in Table 1 is 1.25/1.28 for Leg 1 and 1.30/1.32 for Leg 2, the SBBO for the order would be +2.71/-2.62 (the bids and asks for Leg 2 would be multiplied by the ratio). Since buying one complex order in this example constitutes buying 1 call at 260 and selling 3 calls at 270, the buyer sells more contracts and the net best bid is positive.

Methods for Matching Orders

With custom-defined complex orders containing up to a dozen legs, matching buyers and sellers can be a challenge. In options, exchanges remedy this by listing them in separate complex order books. However, the dominant player in US futures, the CME Group, lists complex and outright orders on the same feed. In either case, they’ve developed order matching solutions to support liquidity in complex markets.

Exchanges will first try to fill complex orders as complete, leg-for-leg matches with existing limit orders. For products or time periods with lower liquidity, they may look to implied orders or auctions. An order filled as an implied order means limit orders listed in the simple book or outright market matched all of the legs in a complex order.

Alternatively, exchanges may hold a complex order auction when a new order is executed at an improved price from the current SBBO. For 100 milliseconds, an auction presents the order with its contra order, and the market is invited to make offers within the net price of all legs. Participants with resting orders can choose not to update their orders during this auction period.

When entering a multi-leg transaction all at once is not possible or advantageous, a trader may leg-in the order, entering each leg as a single transaction. It can be useful for illiquid instruments but risks slippage for subsequent legs.

Market Data for Complex Orders

Successful complex order trading depends on the right market tick and reference data to ensure a strategy accounts for market dynamics. In US options trading, the consolidated feed from the Option Price Reporting Authority (OPRA) reports complex options last sale data rather than quotes, making direct proprietary feeds all but required to trade complex orders. To get a consolidated view of orders across multiple exchanges, market makers and brokers often construct a user-based best bid and offer (UBBO) from their selection of direct feeds.

In contrast of options feeds, the CME Group’s futures exchanges list spreads and outright orders on the same feed (spread products are listed by their difference, e.g. /ESZ9-ESH0). The challenge with these feeds is that they are divided into channels by data type; the price book and order book for a CME feed are subscribed to separately.

When sourcing the market data for complex order strategies, awareness of these nuances is important to qualifying market data providers. Not all vendors write their feed handlers to include all of the channels offered by CME or cache the asynchronous reference data needed to trade in a complex order auction. Some providers have even built a custom UBBO to shorten firms’ time to market. Understanding the market structure and your firm or trading desk’s specific market data needs is crucial to sourcing data for a successful complex order trading strategy.