ETF Tax Efficiency — The Other ETF Magic Trick

One of the substantial advantages of ETFs for market participants in the United States is their tax efficiency. The structure of exchange-traded funds—specifically the way in which shares are created and redeemed—results in lower overall capital gains taxes for the funds, an advantage passed on to shareholders.

But beyond achieving general tax efficiency, the ETF creation/redemption process can be a tax optimization boon for the main players in exchange-traded funds’ primary market—the providers of the funds and the authorized participants (APs) who serve as liquidity providers for ETFs. The benefits of deferring capital gains taxes can extend to both entities’ larger portfolios.

Refinements approved in 2019 to the regulations that govern US ETFs will make it even more efficient for APs to engage in the transfers of securities baskets for ETF shares that deliver that tax optimization to institutional investors.

Creation/redemption transactions can be simplified by automating basket calculations with high-speed computational technology designed to total the Net Asset Value (NAV) of hundreds of stocks in an ETF and keep up with real-time changes that occur thousands of times a second.

The ETF Edge: Liquidity, Transparency — and Tax Efficiency

Retail investors are increasingly moving to exchange-traded funds, whose unique structure gives them advantages over more established mutual funds. Because ETFs can be traded on exchanges like individual stocks, they are more liquid and their prices more transparent as they change over the course of a trading session. In addition, ETFs generally generate lower administrative costs.

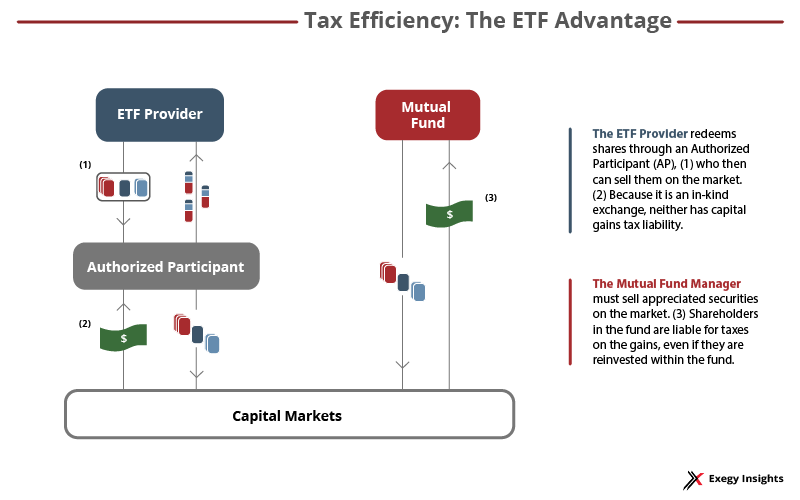

Tax efficiency is a major driver of US ETF activity and is baked into the system by which new shares are created: APs, who may be market makers, large investors, or institutional broker-dealers, bundle the component securities for a particular exchange-traded fund, and give the resulting basket of securities to the ETF provider, exchanging it for shares in the ETF.

These transactions are used by ETF providers to do the necessary rebalancing of their funds. Since they don’t involve cash, they generally don’t generate capital gains tax liabilities for the fund.*

Mutual funds, by comparison, must complete the same rebalancing by buying and selling securities. This may result in more capital gains—and the taxes that go with them.

In general, ETFs are also more passively managed than mutual funds, often tracking an underlying index. This leads to less need for rebalancing, again generating fewer taxable transactions. Yet even when comparing actively managed ETFs to their mutual fund counterparts, the tax savings are significant.

Up to a third of US professional investors surveyed in 2020 by J.P. Morgan Asset Management cited tax benefits as one of the most important attributes of ETF products and strategies. This is significantly higher than in other global markets.

While this tax efficiency is a major selling point in the so-called secondary market (the sales of ETF shares to individual investors), the real alchemy of ETF tax optimization takes place in the primary market, where ETF providers and APs can leverage the unique tax benefits of creation/redemption to manage their overall capital gains tax obligations across their holdings.

The ‘Heartbeat’ of ETF Tax Optimization

At the heart of this more complex, more profitable tax advantage is a provision in a 1969 law originally intended to help boost mutual funds. As a result of that provision, an ETF provider can distribute appreciated stock to investors who are withdrawing from a fund without triggering capital gains taxes.

This goes further than simple creation and redemption. Using this ability, an ETF provider can choose which stocks in the fund’s portfolio to distribute to APs based on the tax effects; if they select stocks that have gained value, they avoid those assets’ potential tax liability.

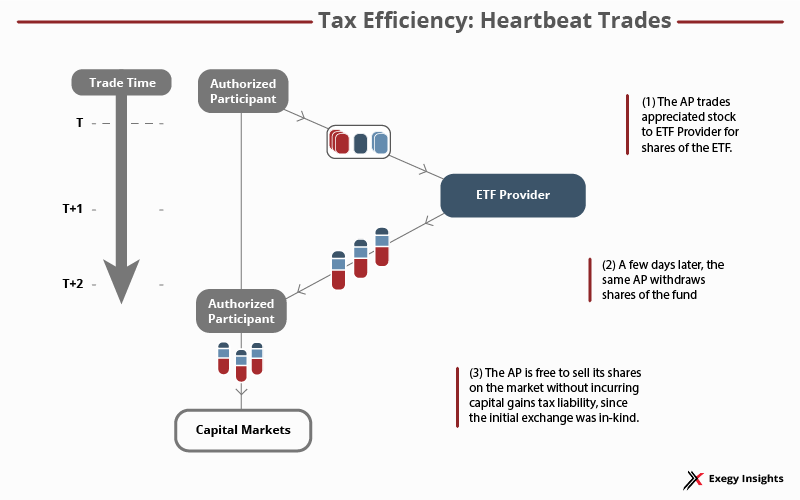

To create even greater tax efficiencies, ETFs can work with APs to make what’s called heartbeat trades. In these transactions, an AP will deposit securities into a fund for a short time—as briefly as a few days—then withdraw a different stock, which has appreciated in value. The trades are generated for the sole purpose of avoiding taxable gains. The trades are named for the telltale “heartbeat” blips like those on an EKG tape indicating large, short-term equalized flows in and out of an ETF. They often take place in the period around a rebalancing (inflows in the days before, and outflows after) and have allowed some of the largest equity ETFs to cut capital gains taxes to zero.

In fact, an ETF provider can even minimize taxes from an associated mutual fund, pulling appreciated stocks from the mutual fund to use in the ETF’s heartbeat trades. Vanguard has patented its method for this practice, which has been described by some as a tax “dialysis machine.”

And both sides of the heartbeat transaction can leverage this tax optimization ability. An AP who holds a number of appreciated stocks can present them as a basket, exchange them a few days later for ETF shares and pay no capital gains tax on the appreciated value. This gives them a powerful added incentive to participate in the primary ETF market and to promote ETFs to their retail customers, whose demand for shares will impel ETF providers to engage in more creations.

As the tax benefits of this symbiotic relationship between providers and APs spurs growth in the ETF industry, US regulators have overhauled the rules governing ETFs to better manage that growth.

Regulations add Flexibility

In 2019, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) adopted Rule 6c-11, with the goal of modernizing the way in which US ETFs were regulated. Previously, ETFs had to get exemptive orders from the SEC to operate, which added time and expense to the process. Rule 6c-11 speeds up that process and standardizes the requirements for existing ETFs.

This rule, and some accompanying orders, include a number of upgrades to the existing ETF regulations, but a few in particular revolve around the all-important creation/redemption process that underpins ETFs’ tax advantages. They focus on the baskets of securities that are exchanged for ETF shares between ETF providers and authorized participants:

–Rule 6c-11 gives ETF providers greater flexibility in how they use custom baskets—baskets that may not strictly reflect a pro rata (proportional) slice of the fund’s portfolio holdings. Because some constituent securities in a large fund may not be as liquid, it is not always optimal to create a pro rata basket. Early ETF exemptive orders allowed a wide latitude in providing non-pro rata baskets or partial cash substitutions; more recent orders were more restrictive. With this rule, all ETFs are playing on a more level field.

To comply, ETFs must submit detailed requirements for how these baskets can be constructed, based on the best interests of the fund and its shareholders. Armed with this added flexibility, newer ETF firms can increase their participation in the lucrative heartbeat trade alchemy.

–In late 2019, the SEC began giving approvals to firms offering semi-transparent active ETFs. Previously, ETFs generally had to disclose complete holding information (underlying assets and weightings) daily.

In seeking approval for less transparent ETFs, each firm had to offer a method of making information about the fund’s holdings available to APs to facilitate creation/redemption. The methods of creating these proxy baskets vary, from using different weightings to creating a second-by-second verified intraday indicative value (VIIV) to approximate the basket.

This move makes ETFs more appealing to active managers, who resist divulging their “secret sauce” and potentially opening themselves up to front-running. The development has led some asset managers to begin converting existing mutual funds to ETFs, and experts predict more conversions will follow.

Leveraging ETF Tax efficiency with basket calculation

While these changes give ETF providers and APs more flexibility and opportunities, they also make the process of valuing baskets even more complex. In a fund containing hundreds of securities, all with the potential for thousands of price changes per second, the computing demands can be immense.

And as we noted in a previous post on ETFs, firms must be mindful of the spread between a fund’s price and its NAV; the cost of getting on the wrong side of that spread could easily outweigh a fund’s tax benefits.

A robust basket calculation engine (BCE) can make the difference in keeping up with the fast-paced ETF industry. The Exegy Ticker Plant is outfitted with a BCE that can calculate NAVs for thousands of securities with the additive latency of a few hundred nanoseconds. As asset managers increasingly turn to ETFs as a source of tax-efficient diversification, firms must ensure that their infrastructure is up to the task. To review your firm’s readiness and how we might help enhance it, contact us.

*The tax efficiencies of ETF structure do not apply to every type of ETF, including those based on derivatives and those operating in countries that do not allow in-kind transactions. Tax issues can be complex; consult a qualified tax professional to discuss your firm’s unique situation.